I love painting faces. Every face is a new challenge. As I become more and more absorbed in the task, years of studying facial structure, expression, color theory, watercolor technique, and anatomy emerge and seamlessly offer me solutions to problems one stroke, one moment at a time. I feel like a painting superhero.

And then when it’s over, it’s…over. I go back to thinking about the energy bill or washing dishes or doing the laundry. Life continues.

This experience is common to all people, and yet it yields uncommon results. It has been called by many names, such as “the zone” or “the pocket.” Scientists have another name for it: Flow.

Undoubtedly, you’ve felt this while painting. Perhaps you go for a while without it, and start to wonder why you keep working; and then, one day, you become so absorbed in the process that you lose track of reality and your surroundings. Tiny, repetitive textural strokes become endlessly entertaining. Planning and executing large washes is a breeze. All of your methods synthesize effortlessly, and before long, you’re looking at work that’s a degree better than your typical product.

Flow occurs while athletes are performing, when musicians are improvising, and when artists are creating. Not always, however – while these optimal states of consciousness appear to be responsible for the highest levels of human performance, they don’t happen automatically. That leads to the question: how can we trigger Flow in our work?

Neurosience Professor Dr. Arne Dietrich coined the term “transient hypofrontality” to describe an aspect of Flow: rather than being a form of hyperfocus, our frontal lobes (the areas of our brain responsible for conscious thought, sense of self and perception of time) actually slow down. That’s why hours pass unheeded when we’re in this state. You’re focused, but not in the sense that your brain is firing on all cylinders; rather, it’s shutting out all the unimportant stuff and working its magic.

So again, the question: how can we achieve Flow on a regular basis?

Scientists are beginning to determine and study a variety of triggers for Flow, but today I’d like to offer you the only one that has worked for me with any real consistency: the Pomodoro Technique.

The Pomodoro Technique was created by Francesco Cirillo and named after the tomato-shaped kitchen timer he used to implement it (pomodoro being the italian word for tomato.) It goes like this:

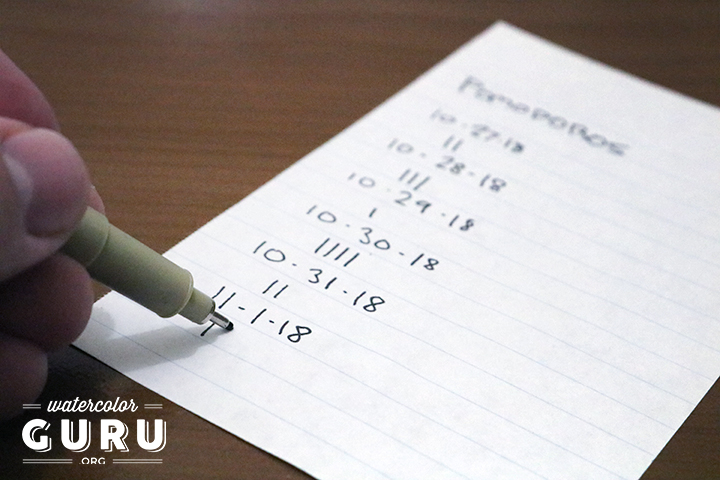

Choose a task and set the timer for twenty five minutes (one pomodoro.) Work on the task singularly, whole-heartedly, until the timer goes off. Add a tally mark to a piece of paper and take a five minute break.

When the five minutes are up, reset the timer and work for another twenty five minutes. When that pomodoro is done, add a tally mark and take another five minutes off.

When you have four tally marks, take a thirty minute break. Continue until the task is done or you have to stop.

This is by far the best way I’ve found to consistently achieve flow, but there are some requirements. Here are my rules:

- Absolutely no multitasking. For twenty five minutes, nothing exists in the universe except you and your painting.

- Once you start the timer, nothing can be allowed to distract you. I make sure to use the bathroom and take sips of water between pomodoros, because I won’t do those things while I’m working. I will not check the weather or send an email. The stock market does not exist. The person trying to get my attention can wait. Unless the house is burning down around you, do not break concentration. Even then, why just stand around waiting for the fire department to arrive? You could bring your painting outside and continue working (kidding, of course.)

- No Instagram. No Facebook. No YouTube. Don’t look at your phone.

- Do not check how much longer you have in the pomodoro.

- I recommend music off when you’re first working on your drawing or painting. When you get to the more repetitive tasks, like adding texture or details, music can be acceptable. Audiobooks and podcasts are also great.

- I’ve described the traditional Pomodoro Technique, and that’s what I use; however, a very accomplished friend of mine does fifty-minute pomodoros with ten minute breaks because he feels like twenty five is too short. If that works better for you, then fine. Just do the work.

How do you know if you’ve achieved Flow? My metric is how I feel when the time is up. If I think, “finally, now I can eat some cheese” then I never really achieved flow. If I think, “dang, twenty five minutes already? Ok, let me just finish up this one area” then I know that my prefrontal cortex and its regulation of time shut down and I reached “the Zone.”

Adam Ondra, the world’s best rock climber, said that “the fight with your mind is the one you can win only temporarily.” Sadly, there’s no magic word you can say or switch you can flip to achieve Flow; you have to start over from scratch, every single day. The good news is, once you know that Flow is the goal, you can systematically pursue it rather than haphazardly painting without purpose.

What is your best experience of Flow? Have you ever (pleasantly) surprised yourself with a painting achievement? Let me know in the comments.

Also, if this article was interesting to you, then your friends might find it interesting as well! Why not pass it on? Flow states are a relatively new branch of neuroscience, and I think they should get more attention than they do, at least among artists. Let’s all get better together!

————–

For more thoughts on time management, check out this previous post.