For the purpose of this article, I’m assuming that selling your work is something that you’d like to do. If you make art for love, and not for money, I respect that, but this article isn’t for you.

The most important thing you need to know is that art functions based on the same economic principles as everything else, with one exception: whereas nearly all businesses and resources have some sort of price cap placed on them by the government, art does not. Therefore, art prices can inflate upward indefinitely, as in the case of the $450,000,000 sale of Salvator Mundi by Leonardo da Vinci.

While I’m by no means an economist, here are a few basic concepts to understand:

An economy is a system used to distribute scarce resources. An in-demand resource only becomes valuable because there’s a limited amount of it; you don’t have to buy air because it’s all around you.

Value isn’t real. Think about it; if I trade you a dollar for a bottle of soda, that trade is only possible because I believe the soda is worth more than the dollar, and you believe the dollar is worth more than the soda. If the soda actually had a set value, then one of us would be getting ripped off; trade is only possible because value is an illusion that we all believe in.

Therefore, art is only worth what someone is willing to pay for it. An artist may reason that their masterpiece is “worth” $10,000, but if no one buys it at that price, it’s not worth 10k.

Here’s a personal example. Recently, a lady mentioned to me at a show that I needed to raise the prices of my art.

I gestured at the rest of the show. A lot of great artists had entered excellent pieces, and yet, there were no red dots to indicate that they had been sold. Of all the solid work that was in that room, no one was selling anything. Why?

My observation is that it’s because all of those artists were calculating their prices based on what they imagined their work to be worth, rather than what the market would actually pay for.

Imagine you create a piece you’re pleased with. You get a custom frame for it, which sets you back $80. You enter it in a show whose admission fee is $60. Excluding materials, your non-temporal overhead is now $140. You know that if the piece sells, the venue will take 40% of the piece’s price. You decide at first to price it at $300, but then you realize that if the venue takes their 40% ($120) and you already paid $140 to get it where it is, then you’ve only profited $40!

Murmuring underneath your breath about the injustices of the art world, you double the price to $600. Now we’re talking! If the venue takes their $240, that leaves you $220 after overhead.

You enter the show, eager to collect your check. And then…

The piece doesn’t sell.

You watch, nervously, as attendees casually glance at the piece, say something to their spouse about how expensive art is, and then walk away.

Defeated, you finally take the piece home, where it and its custom frame collect dust.

Here’s the thing: whether you had priced your piece at $300 or $600, you had already spent the $140. That illustrates the fact that when you’re making things, costs are inevitable. No one gets to play this game for free.

The difference is, if you had placed the piece in the show for $300, and sold it, you would have recovered your costs, and even put a little money in your pocket. Another person would have your work on their walls. They would show it to their friends. They’ll be looking for you at the next show, wondering if you’ve made anything else worth purchasing.

What’s more, when you sell a piece, you learn something; you learn about who your target demographic is, what they like, what kind of words they use. You learn that your price is reasonable, that your work is indeed “worth” that price point. But if you don’t sell, you learn nothing: you’ll never know if it’s because your work is too expensive, or didn’t resonate with anyone emotionally, or some combination of both.

Never price your work based on what you think it’s worth. Always price your work based on what someone will be willing to buy.

Where to start and how to know if you’re doing it right.

At this point, it may seem like I’m advocating that you sell your work for less than it’s worth, playing the low end of the market. That’s not the case at all; what I’m saying is that price is just an outer reflection of scarcity and demand. If you’re a globally-renowned artist, you may be able to charge tens of thousands of dollars for your pieces.

But of course, you can’t start there. Instead, begin by making pieces that you can sell in the $50-$150 range. If you’re selling at that price point, fantastic; you can start to gather data about your market. Continue working to increase your skills and your renown.

On the other hand, if you sell nothing at all, regardless of how it’s priced, then it might be that your art just isn’t appealing to people yet. Remember, Van Gogh never sold anything in his lifetime, perhaps because his work simply wasn’t pleasing to anyone’s eye. You may admire Van Gogh’s work, but again, I’m assuming that you’re reading this article because you want to sell.

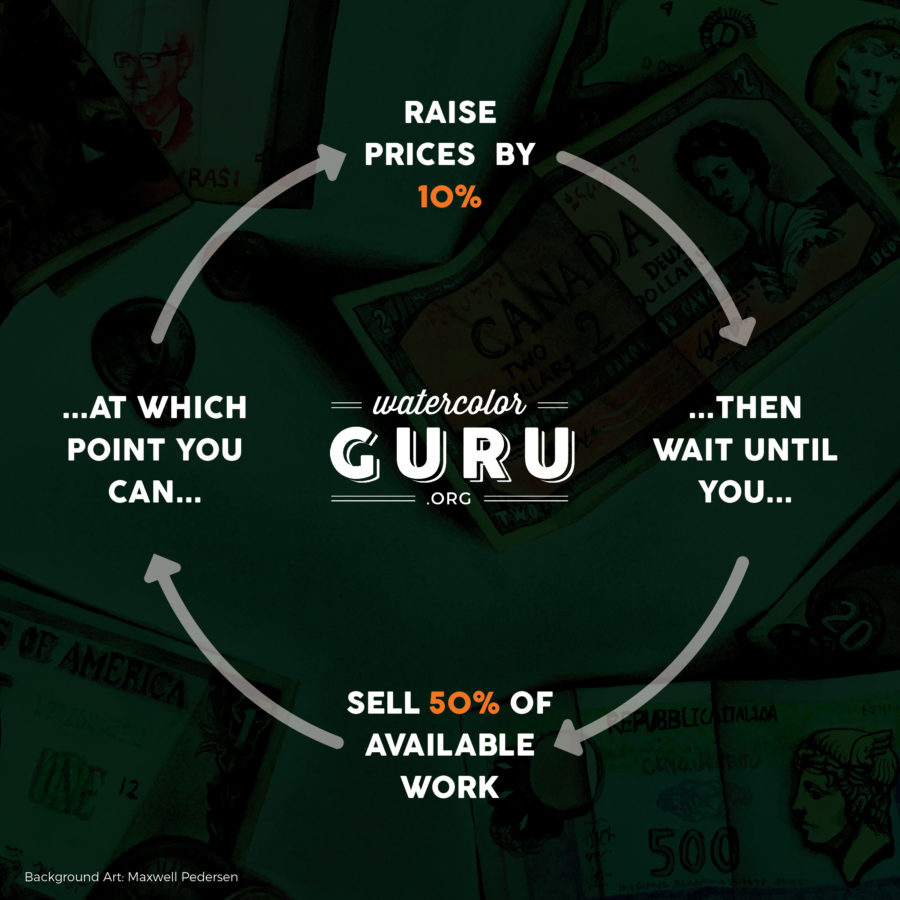

When should you raise your prices? As a rule of thumb, I recommend that you wait until about half of the work you make sells. That’s an important benchmark, and when that happens, you can raise your prices about 10%. Once half of your work is selling at that those prices, raise them again. Most elite artists are ultimately able to sell their work for between several hundred and several thousand dollars. Beyond that is the realm of the world class; people like Guan Weixing or Mary Whyte, who can sell their paintings for $30,000 apiece or more.

If you don’t reach the 50% benchmark immediately, don’t worry. This world we live in trains us to want instant success; and yet, success in the most important endeavors takes time. It may be years, or even decades, before you reach this point. You may never reach that level; and that’s okay. Just keep working.

Key Takeaways:

- Start with small to medium sized pieces that you can sell for $50-$150.

- Once half or more of those pieces sell as quickly as you make them, increase your prices by about 10%.

- Continue to improve your work, network with other artists, seek showing opportunities, teach, and generally increase your fame. As the demand for your work increases, so will the scarcity, and therefore the perceived value.

- Make the kind of art that speaks to you, but realize that it has to be pleasing to the eye. No one will buy CD’s from someone whose music is obnoxious, and no one will buy your work if it’s ugly.

That’s it! For a more general discussion of how to make money painting, check out the previous article on that here.

For all you fantastic artists reading this, what has and has not worked for you? What paintings have sold well? What’s bombed? Leave your thoughts in the comments. Let’s all get better together!